Semaglutide for heart attack & stroke prevention: miracle drug or usual marketing trickery?

Popular media reports 20% improvement in cardiovascular illness and deaths. A few positive results don't get any press for some unfathomable reason.

[Apologies for the multiple revisions; what else would you expect from what is essentially a half-assed hobby of mine? If you’re expecting a professional product, you’re decidedly in the wrong place.]

First the disclaimer: I did not set out to disparage Novo Nordisk’s drug, but as I unravel the story it’s leaning that way.

Semaglutide (Wegovy, Ozempic and other trade names) is a popular weight-loss drug that has been in use for several years. Late in 2023, a lengthy (~ 4 years) trial was published in the New England Journal of Medicine. Unlike earlier trials that tested weight loss, this trial examined benefits against heart (cardiovascular) disease in older, obese patients with history of CVD.

Based upon a study that was published in late 2023, in the past few months its results have been appearing in popular media. Here’s a typical favorable article:

https://www.cnn.com/2024/05/13/health/wegovy-trial-analysis/index.html

My interest was piqued, not because I’d use the drug, but because I thought I might invest in the manufacturer, Novo Nordisk. But I also possess a passing interest in health issues, and have read Kendrick (as shown in my other articles on this site.) From his book Doctoring Data I’ve learnt some of the tricks that are played with clinical trials. Since this is a textbook case of the media touting a new drug, replete with claims of how good it is, I’ll put my admittedly limited sleuthing skills to the test.

With little effort, I located the official study:

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa2307563

Now at first I was unable to look at the entire study as it was a paid item, but was pleasantly surprised to find I could access it via Google Scholar for some reason. Here’s the link I used:

Now I won’t delve too deeply into where and how to look for stuff. You can read Kendrick or some other source for that. What is needed is this disclaimer: I am very much the amateur and it’s quite possible that I make mistakes.

Since this is intended to be a brief essay, I’m only giving the bare numbers. You are free to look in the actual study to verify the numbers and confirm or more likely, refute my “findings.” I do make mistakes, and I don’t have anyone to check my work. Handful of readers, I’m counting on you!

All the trial participants were obese, had prior history of cardiovascular disease, and had an average age of about 62. About ¾ were male. While prior CVD portends more heart disease, the trial excluded diabetics which would counteract that somewhat.

Overall, the media seems to have accurately reported what the trial found. In round terms, there’s a 20% reduction in heart attacks and strokes and the like.

But Kendrick “taught” me to look at all-cause mortality. If it’s not reported it probably didn’t change. Now he probably meant in the formal paper, not in the mass media cheerleading. And this is where it gets a bit weird.

As this skeptical article

says, “No all-cause data at all are presented [in the abstract], not even for mortality. As we saw with the trials for the Covid-19 mRNA injections, this can hide a multitude of issues. Mortality or hospitalization, or other serious adverse events, could be substantially higher in the active group compared to placebo, but we wouldn’t know.”

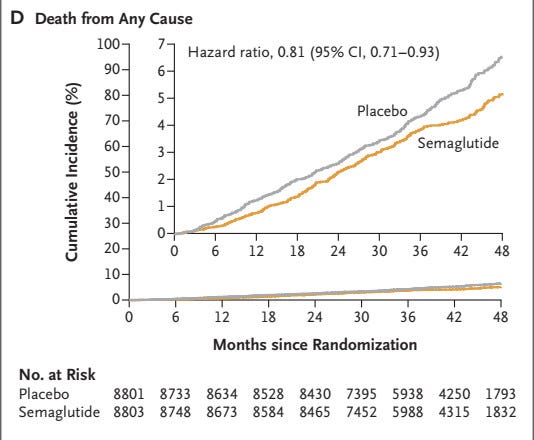

The full study does, in fact, report all-cause mortality. They call it “death from any cause.” You’ll find it in Table 2 on page 7. (The hazard ratio is 0.81; don’t worry if you don’t know what that means, I scarcely do myself! But simply it means that with treatment, there is a 19% reduction is deaths from any cause.) Quite to the contrary of what HART quote (above) asks, I would think that a reduction in death from any cause, not just CVD, would be mentioned, but I can’t find it either in the NAJM study nor in the articles.

Most of the following figures come direct from NAJM paper. I’ve reproduced one graph from that paper, since it’s a main data source for me.

Table 2 entry, placebo, death from any cause, says that 5.2% died over some time period. I’ve seen different durations in various places in the report, but I’m using 48 months which is found in Figure 1D on page 6 (reproduced below). Using this chart, I arrived at a value of 6.5% by manually marking a paper copy of the study. Right there is the first discrepancy: 5.2% ≠ 6.5%.

If that is correct, it means that the placebo group had an annual all-cause death rate of 5.2/4 = 1.3% or is it 1.6%? That made my Spidey sense tingle and here’s why.

Remember that the test subjects are an unusually sick group. Let’s look at the annual death rates of “normal” people. Here’s a handy dandy link to Social Security’s data:

https://www.ssa.gov/oact/STATS/table4c6.html

To keep things simple, I only used male, aged 62 since that’s (almost) the average test subject’s age. I get an annual death rate of 0.016484 = (rounded) 1.65%.

For a while I thought that the reported death rate was deceptively low. After further consideration perhaps not. I’d assumed that the participants, since they had known prior CVD, should expect a high death rate (compared to entire population.) However, since diabetics and some other conditions were excluded, this would tend to make the participants “healthier” than the general population, of which about 25% are diabetic. I lack the detailed analysis tools to investigate the underlying rates in any better detail, so I’ve decided to accept the death rate as reported in NAJM. I suppose it’s possible that fat slobs with CVD history but without diabetes are, on avearge, as healthy as the overall population which includes one-quarter diabetics (as well as fat slobs).

Trickery Seems Unlikely

In my initial foray, I suspected deception in the deaths from any cause figure. But perhaps not. Now, clinical trials are quite rightly held in some degree of disrepute for risk of bias, distortion and at times outright fraud. No claims, even if they come from “respectable” sources, should be taken without a grain of salt (preferably sodium chloride USP, tested for efficacy against credulity in a placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blind study.)

Yet I had this insight: That doesn’t seem applicable to the anomaly I’ve found, that test subjects who’d be expected to have a higher overall death rate than the general population don’t, and indeed seem to have a slightly lower rate. Yet, if that is a deliberate falsification, to what end? Neither the authors of the study, nor the reportage in popular media, appear to make any mention at all of the lower deaths (except for reducing cardiovascular deaths.) If I’ve really uncovered what seems an unrealistically low death rate, perhaps it’s a sign of sloppiness, not deceit. At this later date, I think I was just chasing a shadow. There is some goofiness in the study’s numbers, but they are garden variety Pharma fuckery as I’ll detail below.

Daily Sceptic Article of May 22

This is offered as a refresher about standard deceptive claims of many drug studies. No mention of “my” strange finding, though.

https://dailysceptic.org/2024/05/22/are-we-being-told-the-full-story-on-ozempic/

My further semi-research

Nearly 25% of Americans aged 65+ have been diagnosed with Type 2 Diabetes. Since Type 2 is by fair the most common, we’ll round up to 25%.

Diabetes increases the risk of CVD 2-4 times (call it 3x) compared to non-diabetics.

A history of prior CVD imposes a similar risk as does diabetes.

In US roughly 20% of all deaths are cardiovascular related.

In study, trial participants’ death due to “cardiovascular causes” (Table 2) is 3.0/5.2 = 57.7% of all deaths. (Again, that’s from Placebo group). How much more common is it than the overall population? Easy: 57.7/20 = 2.885 times, very close to my 3 estimate above.

Equivalently, I can say using figures derived from Table 2 that trial participants have multiple risk factors for CVD except for diabetes and a few other factors, such as very recent CVD event.

If 6.5% of subjects died in exactly 4 years, that likely means that Table 2’s duration was (5.2/6.5)*4 = 3.2 years = 38.4 months. Does that figure appear in the text?

If it’s true that diabetes risk is roughly same as prior CVD, does that mean it’s a “wash” with the subjects? In other words, their heart disease risk is reduced because there are no diabetics. On the other hand, their risk is increased because they all had prior CVD. Problem: in overall population there will be overlap between those groups. How to deal with this? My brain hurts. We’d have to know the population of each one, and I don’t have that level of detail available.

I’ve pondered this a bit more, and now am leaning to the possibility that the study subjects’ all-cause death rate is as reported. At first I thought it suspicious, being virtually the same as the overall population’s. Now I realize that excluding diabetics (and several other health conditions) from the trial population will dramatically reduce the death rate. The main thing that’d increase their death rate is probably the history of prior CVD. Study populations are chosen for various reasons, and the inclusion/exclusion criteria can have dramatic differences upon the morbidity and mortality rates. For example, I found an aspirin study

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6433466/

whose test population was very healthy (averaged) 70-year-olds with no known health issues. Their death rate was 1.11/2.7 = 41% or nearly 1/3 that of the comparable overall same-aged population. (As an aside: that study found that aspirin actually increased the all-cause death rate a bit, primarily due to cancers.)

I grudgingly concede that the NAJM paper’s reported death rate may well be valid. To verify it, I’d need detailed analytical tools and knowledge that I lack. Still, it’s fun to stir the pot. It’s not like Pharma has a squeaky clean reputation. They don’t just have a skeleton in their closet; they have an entire ossuary, a network of catacombs under the building. Nevertheless, the medical system can and does deliver products that actually treat illness and even cure it sometimes.

Errata

An earlier version of this essay reported that semaglutide is off patent. I jumped to that conclusion because of this article. The new conclusion I’ve jumped to is that the active ingredient (semaglutide) is still proprietary, but can be sold to compounding pharmacies who can sell a medication at a slightly less exorbitant price.

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-13439425/viagra-weight-loss-budget-ozempic-drug-shortage.html

Despite my prior learning, I briefly fell for the “20% reduction” claims, again!

Thanks to the writer (and the commenters) on the above-linked HART article. It awakened me to the fact that I’d actually posted favorable comments about the relative risk reductions found in the study. Oh, they’re probably real enough... But I’d forgotten the fundamental lessons of Kendrick and others: Usually, one needs to look at the absolute risk reductions to find out how valuable a drug’s effect really is. So, a bit on that to conclude this latest, greatest, revised version of my essay.

Surely, a drug that can deliver a 20% reduction in heart attack and stroke in a high-risk population (secondary prevention) is not to be sniffed at. And equally laudable should be similar reductions in cardiovascular death (15%) or death from any cause (19%). Well, yes and no. As is usually the case, these clinical trials make a mountain out of a molehill. For the rest of this section, I’ll only consider the death from any cause to work the example, but the math (and the results) would be similar for any other risk reduction given in the study.

The study reports a hazard ratio of 0.81 in Figure 1D. OK, my placebo group had a death rate of 6.5% over 4 years = 1.625%/year. Multiply that by 0.81 and you get 1.31625% which should be Treatment’s annualized death rate. So the absolute risk reduction is 1.625 – 1.31625 = 0.30875 ~= 0.31 = 31%.

Now with that number we can finally find out the dirty laundry that studies never report, but is useful for assessing the actual cost and value of a treatment. Here goes.

NNT (number needed to treat) = 100/0.31 ~= 323. Briefly, that means you’d need to treat 323 patient-years to “save” (delay, really) one death. This can be equivalently stated a few different ways. Or, in the course of one year, 322 patients taking the drug would derive no benefit, but one would (he would’ve died but he lives another year.)

Cost-benefit: This is the downer part. Let’s assume that the drug costs $100/month. In that case, to prevent one death you’ll need to treat 323 patients at $100/mo. Times 12 months, at a cost of nearly $388,000 to prevent one death. That’s rather expensive.

Utility of Semaglutide (as prevention) probably in same range as the statins

A NNT of 323 is broadly speaking in the same range as the statins. Here’s a link to one of my better articles (in my opinion) that examines one such drug. It’s worth mentioning that the study in question (JUPITER) actually found better numbers than was typical for most of the statin clinical trials.

https://satansdoorknob.substack.com/p/different-views-of-the-truth-drug

Bottom Line: These drugs work, but…

Semaglutide joins a very long parade of drugs that are rolled out to great fanfare. Most of them “work” to some extent, but there are often hidden side effects. There are, to be certain, always the economic costs, which is why Pharma and its minions so heavily promote them. Jaded skeptic that I am, I still got enamored, even if just a bit, by the spectacular claims for Semaglutide. But now that I’ve sobered up a bit, it looks like just the latest money maker for Pharma. Will it really become a front-line CVD prevention medication, whether for primary or secondary prevention? I don’t know. If it does, it’ll be expensive for the health care system, though.

Hmmm….maybe I should buy some shares of Novo Nordisk after all.